The view from above: Using drones to map sagebrush ecosystems

Drones and other unmanned aircraft systems bring both an engineering and an ecological challenge to field research.

By Amanda Heidt

February 2025

Nevada is known colloquially as the “Sagebrush State”—a nod to the dominant habitat that covers tens of millions of acres in the state and nearly one-third of the continental United States. And while it can be tempting to view this expanse as a monotonous sweep of land dominated by a single species, sagebrush ecosystems are in fact quite diverse, supporting hundreds of species uniquely adapted to a hot and arid climate.

Given the ubiquity of sagebrush habitat, researchers in the Harnessing the Data Revolution for Fire Science (HDRFS) project are therefore interested in the interplay between these ecosystems and wildfire, including the community of plants that make up a landscape, the amount of fuel those species represent, and what that might mean for the land’s recovery.

Christos Papachristos, the director of the Robotic Workers Lab at the University of Nevada, Reno, and a member of the Cyberinfrastructure Innovations (CII) component of HDRFS, is especially interested in the ways that drones and other unmanned aircraft systems can be leveraged to monitor these vast spaces and predict if and how a fire is likely to burn. One of his projects, called DENDrone, uses autonomous drones to map the “digital ecology” of sagebrush ecosystems and create high-fidelity, three dimensional models of these systems much more quickly and with more reliable accuracy than a traditional field crew.

“If you want to do a highly detailed inspection of a field, you have to either take out a very, very large team or just a few people, but over the duration of multiple days,” he says. “But a robot can systematically map out the exact coordinates of specific plants, autonomously adapt its flying pattern to allow it to produce high-fidelity 3D reconstructions of them, and use AI to characterize specific shrub species in a very fast manner.”

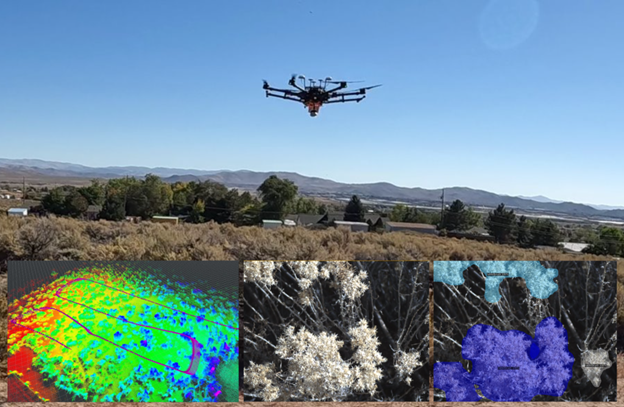

The DENDrone uses LiDAR, GPS, and IMU sensors to map sagebrush landscapes from the air and identify some of the most common plants with up to 90% accuracy. Credit: Prateek Arora

The microwave-sized DENDrone is armed with a variety of cameras and sensors—including GPS, LiDAR, and IMU—that image a landscape from multiple angles, including not just the overhead perspective, but close-up views of individual plants as well. These latter images provide “much richer information about what kind of fire fuel you’re expecting to have,” Papachristos says.

The utility of these data is twofold: the drone is able to create a three-dimensional map of the landscape, but it’s also able to identify some of the plants. Using artificial intelligence and machine learning, the team has trained DENDrone on thousands of images of rabbit brush and sagebrush—two of the most common plants in the habitat that look very similar from above yet have defining leaf shapes and structures—such that the drone can now distinguish between the two with roughly 90% accuracy.

Building DENDrone has been a unique engineering challenge, says Prateek Arora, a PhD student in Papacristos’s lab who leads the design of the drone and data processing framework. Each mapping excursion produces terabytes of data, meaning the group needs a sophisticated model to funnel and interpret their findings. In addition, the drone has been designed with a degree of autonomy through a process called adaptive path planning, meaning it can determine whether it has collected enough data to produce a viable map and adjust its course in real time.

“It’s also just a surprisingly complex system that we’re working in,” Arora says, noting that the field sites tend to be very windy, which causes the navigation landmarks the drone relies on to shift and sway. Making sense of this changing environment also presents a challenge for the drone’s computational capacity, which is limited for now to what can be analysed by the drone’s onboard central processing unit. “To get around that, we’ve been shifting towards doing everything through the cloud, which is something that fascinates us as engineers.”

Andres Andrade, a plant ecologist at the Desert Research Institute (DRI) in Reno, is now helping the team bridge the gap between engineering and biology. The group has already mapped one field site by comparing DENDrone to measurements taken by hand by a traditional field crew, and will soon do the same at the project’s main field site—located outside Reno along Red Rock Road. In 2025, the entire HDRFS team will come together for a series of controlled burns, allowing the DENDrone team to collect information during and after the fires. In preparation, Arora has added a thermal camera to the drone to determine how hot different plants burn and smolder.

The goal, Andrade says, is that DENDrone may one day be able to analyze images of a particular site “and from them predict the major fuel types present, how much fuel is available to burn during a potential wildfire, and the subsequent effects on the ecosystem.”

Answering these questions will require thinking over the long term, in acknowledgement of the fact that landscapes can change significantly from year to year, particularly after a fire Papachristos says. “We expect to do this type of monitoring seasonally in order to tell systematically, over a prolonged period of time, how the environment is changing and how that is going to affect the models that you build.”

HDRFS Digest is a quarterly publication of the Harnessing the Data Revolution for Fire Science Project, which is a five-year research project funded by the National Science Foundation’s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research “EPSCoR” (under Grant No. OIA- 2148788) focusing on enabling healthy coexistence with wildland fire and the mitigation of wildfire danger to human life, infrastructure, and the landscape in Nevada and the intermountain western U.S.

HDRFS Digest is a quarterly publication of the Harnessing the Data Revolution for Fire Science Project, which is a five-year research project funded by the National Science Foundation’s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research “EPSCoR” (under Grant No. OIA- 2148788) focusing on enabling healthy coexistence with wildland fire and the mitigation of wildfire danger to human life, infrastructure, and the landscape in Nevada and the intermountain western U.S.

Acknowledgement: This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OIA- 2148788.

Acknowledgement: This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OIA- 2148788.